May is Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. In his proclamation, President Obama cited the accomplishments of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders and acknowledged the difficulties that members of this community have faced both historically and in the present.

Let’s take a short trip through our nation’s case law to look at some of these difficulties. Your lessons in school might not have given you a complete picture on American history.

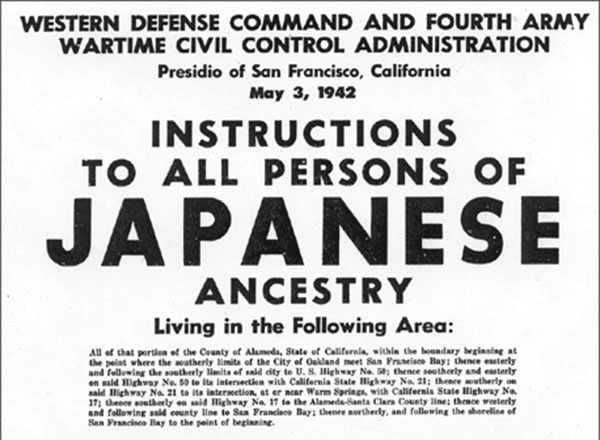

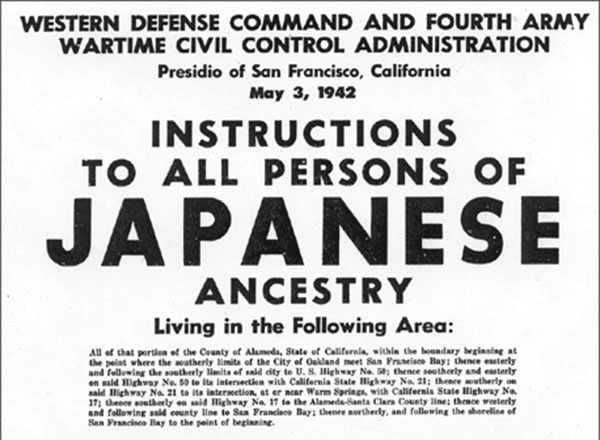

1. Korematsu v. United States

Photo Credit: National Park Service.

Fred Korematsu, an American citizen of Japanese descent, challenged his conviction for remaining in San Leandro, California, in violation of Exclusion Order No. 34, which required all persons of Japanese ancestry to evacuate from a designated geographical area. The Supreme Court stated that “legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group” must be subject to the most rigid scrutiny. “Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can.”

To justify the exclusion order, the Court cited the “definite and close relationship” between the exclusion order and “the prevention of espionage and sabotage.” The Court acknowledged the overinclusive nature of the exclusion order, noting that most of the people impacted by the exclusion order were “no doubt . . . loyal to this country.” However, the Court was not prepared to question the military’s judgment that “it was impossible to bring about an immediate segregation of the disloyal from the loyal” and upheld the exclusion order.

In dissent, Justice Frank Murphy acknowledged the deference that must be accorded to the military in its prosecution of the war. Nevertheless, the order by the military to remove all persons of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific Coast was not reasonably related to its claimed goal of preventing sabotage and espionage because the reasons offered in support of the exclusion order were based not on expert military judgment, but on “misinformation, half-truths and insinuations that for years have been directed against Japanese Americans by people with racial and economic prejudices.”

Even if “some disloyal persons of Japanese descent on the Pacific Coast [] did all in their power to aid their ancestral land,” “to infer that examples of individual disloyalty prove group disloyalty and justify discriminatory action against the entire group is to deny that, under our system of law, individual guilt is the sole basis for deprivation of rights.”

See Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its

By now, you’ve all read that Justice Antonin Scalia made a series of mistakes in the dissenting opinion of EPA v. EME Homer City Generation, L.P. The Supreme Court issued a corrected version of the opinion on its website. For more on the story, read the coverage in the

By now, you’ve all read that Justice Antonin Scalia made a series of mistakes in the dissenting opinion of EPA v. EME Homer City Generation, L.P. The Supreme Court issued a corrected version of the opinion on its website. For more on the story, read the coverage in the  Delaware Courts of Chancery appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court recently, seeking to validate a law that would allow them to hold confidential arbitration proceedings for parties with $1M litigation at stake.

Delaware Courts of Chancery appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court recently, seeking to validate a law that would allow them to hold confidential arbitration proceedings for parties with $1M litigation at stake.  The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC)

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC)  On Monday, in the shadow of then-Hurricane (now-Superstorm) Sandy, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., a case involving the applicability of U.S. copyright law to copies of works created and legally acquired abroad and subsequently imported into the United States.

On Monday, in the shadow of then-Hurricane (now-Superstorm) Sandy, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., a case involving the applicability of U.S. copyright law to copies of works created and legally acquired abroad and subsequently imported into the United States. The U.S. Supreme Court started its term today, hearing oral arguments for Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum. The case involves the interpretation of a federal statute enacted by the first Congress as part of the Judiciary Act of 1879—the Alien Tort Statute.

The U.S. Supreme Court started its term today, hearing oral arguments for Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum. The case involves the interpretation of a federal statute enacted by the first Congress as part of the Judiciary Act of 1879—the Alien Tort Statute. Tomorrow brings one of the most highly anticipated decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court in recent years: the ruling on the constitutionality of the health-care law that is arguably the crowning achievement of President Obama’s first term in office. Incidentally, tomorrow also marks the one-year anniversary of the launch of

Tomorrow brings one of the most highly anticipated decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court in recent years: the ruling on the constitutionality of the health-care law that is arguably the crowning achievement of President Obama’s first term in office. Incidentally, tomorrow also marks the one-year anniversary of the launch of