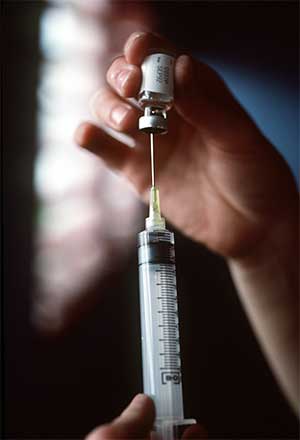

All states require children to be immunized or to be in the process of receiving immunizations against certain contagious diseases before a child care facility or a school may admit them. For each state, the immunization schedule may be found in the state code or its administrative regulations, usually in the sections governing education (for schools) or public health (for child care facilities). Besides specific vaccine requirements, these schedules may also refer to the schedules provided by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, American Academy of Family Physicians, or American Academy of Pediatrics.

All states require children to be immunized or to be in the process of receiving immunizations against certain contagious diseases before a child care facility or a school may admit them. For each state, the immunization schedule may be found in the state code or its administrative regulations, usually in the sections governing education (for schools) or public health (for child care facilities). Besides specific vaccine requirements, these schedules may also refer to the schedules provided by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, American Academy of Family Physicians, or American Academy of Pediatrics.

Where states significantly differ is in their recognition of exemptions from vaccination. All states grant a medical exemption to children who cannot be immunized for health reasons. For example, the administration of a vaccine may be contraindicated in children who are allergic to a component of the vaccine or have a suppressed immune system. These exemptions are specific to the vaccine and health condition, and remain so long as the contraindication lasts.

Additionally, 48 states and the District of Columbia permit parents to claim a non-scientific exemption, such as if their religious tenets or practices conflict with immunization or if their personal, philosophical or moral beliefs are opposed to immunization. The lone holdouts are Mississippi and West Virginia. However, in the event of an outbreak, child care facilities and schools may exclude children who have not been vaccinated against the disease until the end of the outbreak.

Verdict offers some insightful analysis into the issue of religious exemptions:

- How to Craft a Religious Exemption Regime Guaranteed to Be Dangerous for Children:

The Case of Idaho. By Professor Marci A. Hamilton. - The Deep Roots of the Left/Right Anti-Vaxxer Coalition. By Professor Michael C. Dorf.

- The Vaccine for Pollyanna Attitudes Toward Public Health and Religious Beliefs:

Religious Exemptions for Vaccinations and Medical Neglect Need to Be Repealed Now and the Federal Government (and the Insurance Industry) Need to Incentivize the States to Do So. By Professor Marci A. Hamilton.

Below, you will find links to state codes, statutes and regulations governing the immunization of children who attend day care, child care, elementary schools, private schools and colleges.

In 2012, in an effort to combat obesity among residents of New York City, the New York City Board of Health amended the City Health Code so as to restrict the size of cups and containers used by food service establishments for the provision of sugary drinks. The proposed rule, referred to as the “Portion Cap Rule,” was to go into effect in 2013. Six not-for-profit and labor organizations challenged the Portion Cap Rule. Supreme Court, New York City declared the rule invalid and permanently enjoined its implementation. The Appellate Division affirmed. The Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that, in adopting the Portion Cap Rule, the Board of Health exceeded its regulatory authority and engaged in law-making, thereby infringing upon legislative jurisdiction.

In 2012, in an effort to combat obesity among residents of New York City, the New York City Board of Health amended the City Health Code so as to restrict the size of cups and containers used by food service establishments for the provision of sugary drinks. The proposed rule, referred to as the “Portion Cap Rule,” was to go into effect in 2013. Six not-for-profit and labor organizations challenged the Portion Cap Rule. Supreme Court, New York City declared the rule invalid and permanently enjoined its implementation. The Appellate Division affirmed. The Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that, in adopting the Portion Cap Rule, the Board of Health exceeded its regulatory authority and engaged in law-making, thereby infringing upon legislative jurisdiction. By now, you’ve all read that Justice Antonin Scalia made a series of mistakes in the dissenting opinion of EPA v. EME Homer City Generation, L.P. The Supreme Court issued a corrected version of the opinion on its website. For more on the story, read the coverage in the

By now, you’ve all read that Justice Antonin Scalia made a series of mistakes in the dissenting opinion of EPA v. EME Homer City Generation, L.P. The Supreme Court issued a corrected version of the opinion on its website. For more on the story, read the coverage in the  Courthouse News Service

Courthouse News Service  The General Railroad Right-of-Way Act of 1875 provides railroad companies “right[s] of way through the public lands of the United States,” 43 U.S.C. 934. One such right of way, created in 1908, crosses land that the government conveyed to the Brandt family in a 1976 land patent. That patent stated that the land was granted subject to the right of way, but it did not specify what would occur if the railroad relinquished those rights. A successor railroad abandoned the right of way with federal approval. The government sought a declaration of abandonment and an order quieting its title to the abandoned right of way, including the stretch across the Brandt patent. Brandt argued that the right of way was a mere easement that was extinguished upon abandonment. The district court quieted title in the government. The Tenth Circuit affirmed. The Supreme Court reversed. The right of way was an easement that was terminated by abandonment, leaving Brandt’s land unburdened. The Court noted that that the government had argued the opposite position in an earlier case. In that case, the Court found the 1875 Act’s text “wholly inconsistent” with the grant of a fee interest. An easement disappears when abandoned by its beneficiary.

The General Railroad Right-of-Way Act of 1875 provides railroad companies “right[s] of way through the public lands of the United States,” 43 U.S.C. 934. One such right of way, created in 1908, crosses land that the government conveyed to the Brandt family in a 1976 land patent. That patent stated that the land was granted subject to the right of way, but it did not specify what would occur if the railroad relinquished those rights. A successor railroad abandoned the right of way with federal approval. The government sought a declaration of abandonment and an order quieting its title to the abandoned right of way, including the stretch across the Brandt patent. Brandt argued that the right of way was a mere easement that was extinguished upon abandonment. The district court quieted title in the government. The Tenth Circuit affirmed. The Supreme Court reversed. The right of way was an easement that was terminated by abandonment, leaving Brandt’s land unburdened. The Court noted that that the government had argued the opposite position in an earlier case. In that case, the Court found the 1875 Act’s text “wholly inconsistent” with the grant of a fee interest. An easement disappears when abandoned by its beneficiary. HT to Professor Peter Martin who posts in his blog,

HT to Professor Peter Martin who posts in his blog,  Ohhhhh

Ohhhhh  Josh Tauberer

Josh Tauberer  This case involved three Enhanced 9-1-1 (E-9-1-1) calls regarding an altercation that resulted in three people being shot. MaineToday Media, Inc. sent a series of requests to inspect and copy the three transcripts to the police department, state police, attorney general, and others. The State denied the requests, claiming that the transcripts constituted “intelligence and investigative information” in a pending criminal matter and were therefore confidential under the Criminal History Record Information Act. MaineToday filed suit against the State, arguing that the Freedom of Access Act (FOAA) mandated disclosure of the transcripts as public records and that no exception to their disclosure applied. The superior court affirmed the State’s denial of MaineToday’s request. The Supreme Court vacated the lower court’s judgment, holding that the E-9-1-1 transcripts, as redacted pursuant to 25 Me. Rev. Stat. 2929(2)-(3), were public records subject to disclosure under the FOAA.

This case involved three Enhanced 9-1-1 (E-9-1-1) calls regarding an altercation that resulted in three people being shot. MaineToday Media, Inc. sent a series of requests to inspect and copy the three transcripts to the police department, state police, attorney general, and others. The State denied the requests, claiming that the transcripts constituted “intelligence and investigative information” in a pending criminal matter and were therefore confidential under the Criminal History Record Information Act. MaineToday filed suit against the State, arguing that the Freedom of Access Act (FOAA) mandated disclosure of the transcripts as public records and that no exception to their disclosure applied. The superior court affirmed the State’s denial of MaineToday’s request. The Supreme Court vacated the lower court’s judgment, holding that the E-9-1-1 transcripts, as redacted pursuant to 25 Me. Rev. Stat. 2929(2)-(3), were public records subject to disclosure under the FOAA. The Administrative Office of the Courts

The Administrative Office of the Courts