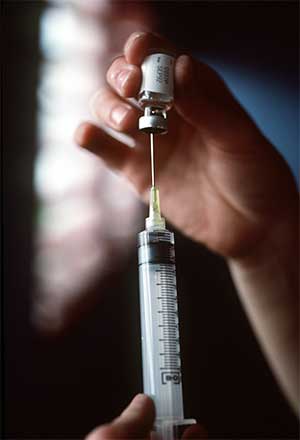

All states require children to be immunized or to be in the process of receiving immunizations against certain contagious diseases before a child care facility or a school may admit them. For each state, the immunization schedule may be found in the state code or its administrative regulations, usually in the sections governing education (for schools) or public health (for child care facilities). Besides specific vaccine requirements, these schedules may also refer to the schedules provided by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, American Academy of Family Physicians, or American Academy of Pediatrics.

All states require children to be immunized or to be in the process of receiving immunizations against certain contagious diseases before a child care facility or a school may admit them. For each state, the immunization schedule may be found in the state code or its administrative regulations, usually in the sections governing education (for schools) or public health (for child care facilities). Besides specific vaccine requirements, these schedules may also refer to the schedules provided by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, American Academy of Family Physicians, or American Academy of Pediatrics.

Where states significantly differ is in their recognition of exemptions from vaccination. All states grant a medical exemption to children who cannot be immunized for health reasons. For example, the administration of a vaccine may be contraindicated in children who are allergic to a component of the vaccine or have a suppressed immune system. These exemptions are specific to the vaccine and health condition, and remain so long as the contraindication lasts.

Additionally, 48 states and the District of Columbia permit parents to claim a non-scientific exemption, such as if their religious tenets or practices conflict with immunization or if their personal, philosophical or moral beliefs are opposed to immunization. The lone holdouts are Mississippi and West Virginia. However, in the event of an outbreak, child care facilities and schools may exclude children who have not been vaccinated against the disease until the end of the outbreak.

Verdict offers some insightful analysis into the issue of religious exemptions:

- How to Craft a Religious Exemption Regime Guaranteed to Be Dangerous for Children:

The Case of Idaho. By Professor Marci A. Hamilton. - The Deep Roots of the Left/Right Anti-Vaxxer Coalition. By Professor Michael C. Dorf.

- The Vaccine for Pollyanna Attitudes Toward Public Health and Religious Beliefs:

Religious Exemptions for Vaccinations and Medical Neglect Need to Be Repealed Now and the Federal Government (and the Insurance Industry) Need to Incentivize the States to Do So. By Professor Marci A. Hamilton.

Below, you will find links to state codes, statutes and regulations governing the immunization of children who attend day care, child care, elementary schools, private schools and colleges.

This complaint concerned the T-65 X-wing fighter plane, a fictional vehicle created in connection with the movie Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Walt Disney Company owned the trademark for the fictional vehicle. Plaintiff developed a marketing plan pursuant to which Disney would license to a non-party the right to use the X-wing name and appearance, the non-party would develop the vehicle in the appearance of an X-wing (the “Flying Car”), and Plaintiff would raise the funds for development of the Flying Car. Plaintiff planned on promoting the Flying Car via tie-ins to Disney’s new Star Wars movie to be released in 2017. Plaintiff made an unsolicited proposal involving Star Wars marketing to Disney, but Disney responded that it was not interested in his proposal. Plaintiff filed this complaint against Disney and its CEO and Board Chairman, claiming that Defendants were “stalling the next evolution of human transportation on this planet.” The individual Defendants, both residents of California, moved to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction, and all Defendants moved to dismiss for failure to state a claim. The Court of Chancery granted the motions, holding that Plaintiff failed to perfect jurisdiction over the individual Defendants and failed to state a claim against any of the Defendants.

This complaint concerned the T-65 X-wing fighter plane, a fictional vehicle created in connection with the movie Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Walt Disney Company owned the trademark for the fictional vehicle. Plaintiff developed a marketing plan pursuant to which Disney would license to a non-party the right to use the X-wing name and appearance, the non-party would develop the vehicle in the appearance of an X-wing (the “Flying Car”), and Plaintiff would raise the funds for development of the Flying Car. Plaintiff planned on promoting the Flying Car via tie-ins to Disney’s new Star Wars movie to be released in 2017. Plaintiff made an unsolicited proposal involving Star Wars marketing to Disney, but Disney responded that it was not interested in his proposal. Plaintiff filed this complaint against Disney and its CEO and Board Chairman, claiming that Defendants were “stalling the next evolution of human transportation on this planet.” The individual Defendants, both residents of California, moved to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction, and all Defendants moved to dismiss for failure to state a claim. The Court of Chancery granted the motions, holding that Plaintiff failed to perfect jurisdiction over the individual Defendants and failed to state a claim against any of the Defendants.