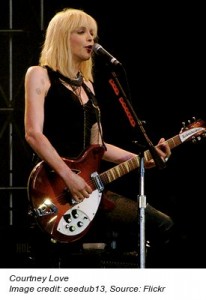

Twitter libel (‘twibel’) cases are growing. Courtney Love just paid $430,000 to settle a twibel case filed by a fashion designer who accused the rocker of defaming her in a series of tweets with incredible accusations. A Welsh politician in the U.K. recently admitted to twibeling his city council opponent on election day. The cost of his settlement? Damages of £3,000, plus £50,000 in legal fees.

Twitter libel (‘twibel’) cases are growing. Courtney Love just paid $430,000 to settle a twibel case filed by a fashion designer who accused the rocker of defaming her in a series of tweets with incredible accusations. A Welsh politician in the U.K. recently admitted to twibeling his city council opponent on election day. The cost of his settlement? Damages of £3,000, plus £50,000 in legal fees.

Although we’re not aware of any twibel case that went to verdict, we’re confident that day will inevitably come.

Libel is a form of defamation, the written kind, where a published statement sent to a third party harms another person’s reputation.

The twibel claims against Courtney Love were particularly shocking. Plaintiff Dawn Simorangkir asked Love to pay for several thousand dollars worth of her frocks. Instead of picking up the phone and talking with the designer to talk about it, the suit charged that Love tweeted to her 40,000 followers that Simorangkir:

- Was a drug-pushing prostitute

- Lost custody of her child

- Committed assault and battery

- Was an “asswipe nasty lying hosebag thief”

- Claimed that she made the designer “famous and g[o]t raped TOO!

Simorangkir sued for libel over the false statements published and distributed to thousands via Twitter that, she charged, harmed her reputation.

It could have been the first American twibel case to go to trial, but the settlement means that another jury in another case may still reach a verdict on defamation via Twitter posts.

Not surprisingly, Love actually cancelled her Twitter account in January before the scheduled civil trial.

The case in Wales, England actually didn’t reach a jury verdict either. In addition to the monetary damages and legal fees, the settlement involved a public apology from the defendant to the plaintiff.

Last September, Twitter said that it had 175 million registered users. Six-month-old figures like that are paleolithic stats for a company whose user base skyrocketed in North Africa and the Middle East when people in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and other countries started tweeting about bringing down their totalitarian governments.

Despite the appeal of Twitter’s 140 character limit, enabling people, businesses, organizations and governments send short missives all around the world, we’ve only just begun to see the tip of the twibel iceberg.